|

Wak Overview |

|

|

|

Genral Information Wak: |

| |

|

|

|

Community information centre Wak's coordinating committee: Today the dated 28 of january 2003,I the operator of community information centre wak conducted a meeting among the panchayats of its surrounding areas and discussed about the following agendas: 1.Smooth functioning of the CIC and its utilization. 2.Ensuring that the user do not misuse the systems in the centre. 3.Ensured them to make aware among the public regarding the facilities. 4.Urged those panchayats to visit the centre once in a week and enquire about the centres functions like accounts,equipments and users. 5.Constituted the committee of three members.Two from the panchayat and one from the centre and gave them the equal status as a member. 6.All the official matters of the centre shall be handled by the respective incharge in consent with the coordinating committee as such no other people can interfere in the matters as far as smooth functioning of the cicwak is concerned beside the departmental personnels but the suggestions and opinions are welcomed in respect to the goodness of the centre. The following constitutes the CIC Wak Coordinating committee: 1.Ashdan Rai,panchayat chumlok. 2.Robin Rai,RDA. 3.Chandan Rai,Centre Incharge CIC Wak. |

|

|

|

|

|

Buddhas saying:"All People Are Buddhas" All People Are Buddhas Niji butsu go. Sho bo-satsu gyu. Issai daishu. Sho zen-nanshi. Nyoto to shinge. Nyorai jotai shi go. Bu go daishu. Nyoto to shinge. Nyorai jotai shi go. U bu go. Sho daishu. Nyoto to shinge. Nyorai jotai shi go. Zeji bo-satsu daishu. Mi-roku i shu. Gassho byaku butsu gon. Seson. Yui gan ses^shi. Gato to shinju butsu-go. Nyo ze san byaku i. Bu gon. Yui gan ses^shi. Gato to shinju butsu-go. Niji seson. Chi sho bo-satsu. San sho fu shi. Ni go shi gon. Nyoto tai cho. Nyorai hi-mitsu. Jinzu shi riki. At that time the Buddha spoke to the bodhisattvas and all the great assembly: "Good men, you must believe and understand the truthful words of the Thus Come One." And again he said to the great assembly: "You must believe and understand the truthful words of the Thus Come One." And once more he said to the great assembly: "You must believe and understand the truthful words of the Thus Come One." At that time the bodhisattvas and the great assembly, with Maitreya as their leader, pressed their palms together and addressed the Buddha, saying: "World-Honored One, we beg you to explain. We will believe and accept the Buddha's words." They spoke in this manner three times, and then said once more: "We beg you to explain it. We will believe and accept the Buddha's words." At that time the World-Honored One, seeing that the bodhisattvas repeated their request three times and more, spoke to them, saying: "You must listen carefully and hear of the Thus Come One's secret and his transcendental powers." (Lotus Sutra, pp. 224 - 225)1 On the Title What associations or meanings have the words Myoho-renge-kyo Nyorai Juryo-hon had for those who, since ancient times, read and recited the Lotus Sutra? Many people doubtless have read through them casually, unaware of their having any special significance. On the other hand, more than a few have passionately engaged in abstract debate on the meaning of the chapter's title. And among these, extremely rare individuals such as T'ien-t'ai of China have correctly grasped the content of the "Life Span" chapter and explained its title on that basis. However, in all of history, no one has ever read the title of the "Life Span" chapter with the clarity of Nichiren Daishonin. The Daishonin says: "The title of this chapter deals with an important matter that concerns Nichiren himself. This is the transmission described in the 'Supernatural Powers' chapter" (Gosho Zenshu, p. 752). Only the Daishonin could read the title of the "Life Span" chapter as "dealing with an important matter that concerns Nichiren himself." And this matter, he says, is closely related to the transmission described in "Supernatural Powers of the Thus Come One," the 21st chapter of the Lotus Sutra. In the "Supernatural Powers" chapter, Shakyamuni entrusts Bodhisattva Superior Practices (Jpn Jogyo) and the other Bodhisattvas of the Earth with the task of propagating the Lotus Sutra after his death. And the essence of the teaching entrusted to the Bodhisattvas of the Earth that can lead all people in the Latter Day to enlightenment is the law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo - the great law of time without beginning - implicit in the depths of the "Life Span" chapter. Nichiren Daishonin possessed Nam-myoho-renge-kyo in his own life. And, as the reincarnation of Bodhisattva Superior Practices, he took the first step to spread the Mystic Law for the people of the Latter Day. That's why the Daishonin says that the title of the "Life Span" chapter "deals with an important matter that concerns Nichiren himself." The title of the "Life Span" chapter also indicates the benefit of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. On this matter, there are a few points that I'd like to mention. The words nyorai juryo in the chapter's title literally mean to fathom the Thus Come One's life span. To fathom the length of the Buddha's life span is also to fathom the vastness of the benefit accumulated by the Buddha. That's because the longer the Buddha's life span, the more people he can lead to happiness and hence, the greater his benefit. Accordingly, T'ien-t'ai says that the term juryo ("fathom the life span") means to measure and elucidate the benefit. In other words, it means to sound out and clarify the benefits of various Thus Come Ones. According to T'ien-t'ai, the benefit of the Buddha specifically consists of the Buddha's three bodies or enlightened properties: the Dharma body or property of the Law (the truth to which the Buddha is enlightened), the bliss body or property of wisdom (the wisdom the Buddha has attained), and the manifested body or property of action (the physical form in which the Buddha appears in this world and his compassionate actions). And he clarifies that the true Buddha - who dwells in this world eternally and possesses the virtue of these three properties - is Shakyamuni who attained enlightenment in the remote past of gohyaku-jintengo. By contrast, from the standpoint of the Daishonin's Buddhism, the fundamental source of the benefit of the eternal Buddha endowed with the three enlightened properties is Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. The benefit of the Buddha who attained enlightenment in the remote past derives from Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Therefore, the Daishonin indicates that the title of the "Life Span" chapter should be read "Life Span of the Nam-myoho-renge-kyo Thus Come One" (Gosho Zenshu, p. 752). President Toda stressed: "The addition - of the [Sanskrit] word nam completely changes the meaning of 'Thus Come One."' When we read the title as Nam-myoho-renge-kyo Nyorai Juryo, it means to fathom the benefit of the "Nam-myoho-renge-kyo Thus Come One"; that is, of the Buddha implicit in the depths of the chapter. Because the Daishonin himself is the Nam-myoho-renge-kyo Thus Come One, he says that the title "deals with an important matter that concerns Nichiren himself." This Buddha implicit in the chapter is said to be eternally endowed with the three bodies. "Eternally endowed" means originally and naturally possessing. The Daishonin says: "'Eternally endowed with the three bodies' refers to the votary of the Lotus Sutra in the Latter Day of the Law. The title of honor for one eternally endowed with the three bodies is Nam-myoho-renge-kyo" (Ibid.). He also says: "'Thus Come One' refers to all living beings. More specifically, it refers to the disciples and lay followers of Nichiren" (Ibid.). If we earnestly chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, then, he says, "in instant after instant there will arise in us the three bodies with which we are eternally endowed" (Ibid., p. 790). How wondrous this is! We can each manifest and sound out the benefit of the law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo implicit in the "Life Span" chapter. From the standpoint of the Daishonin's Buddhism, the "Life Span" chapter sounds out and praises the immeasurable benefit that we who base our lives on the Mystic Law possess. Accordingly, from this perspective, the chapter's title radiates the brilliant light of the Buddhism of the people. Each Day We Reaffirm Our Vow To Propagate the Law Let us now begin our study of the "Life Span" chapter, the very foundation of the Buddha's teachings. The chapter begins, "At that time...." The "Expedient Means" chapter also begins in this way. But in "Life Span," the words carry still greater significance. Namely, they refer to the "time" when the Buddha finally is going to expound the fundamental law of the essential teaching. In other words, the "time" when all people can eradicate fundamental darkness from their lives - the fundamental source of illusion that even highly advanced bodhisattvas such as Maitreya could not easily overcome - has arrived. Moreover, the expression "at that time" in the "Life Span" chapter points to the time after Shakyamuni's passing. And it is for those living after the Buddha's passing that Maitreya beseeches Shakyamuni to expound his teaching. The "time" has at last arrived when Shakyamuni will reveal the fundamental teaching that will illuminate the lives of all people in the world after his passing. That is the "time" to which these words refer. And that's why the chapter opens with a depiction of the solemn drama of the oneness of mentor and disciple. At that time, the Buddha says, "You must believe and understand the truthful words of the Thus Come One." He repeats this statement three times. "Truthful words" are those that directly express the truth to which the Buddha is enlightened. To put it another way, he says he will explain his enlightenment directly, abandoning all expedient means. Therefore, he urges that they receive this teaching with faith. This is the mentor's cry of the spirit, his wholehearted appeal to his disciples. At that time, his disciples beg him to expound it, saying: "We will believe and accept the Buddha's words." The disciples thus earnestly entreat him three times to reveal his teaching. Then they do so yet again. The Buddha understands that nothing can stand in the way of their earnest desire to know the truth. At that time, the mentor begins to expound the teaching never before known, saying: "You must listen carefully and hear of the Thus Come One's secret and his transcendental powers." The Disciple Seeks the Mentors Fundamental Teaching Many sutras describe the drama of the disciples entreating the Buddha three times to expound his teaching. Immediately after Shakyamuni attained the Way, while he vacillated over whether he should begin preaching, Brahma (Jpn Bonten) implored him three times to expound the Law. Similarly, in "Expedient Means," he begins to teach the replacement of the three vehicles with the one vehicle only after Shariputra has made three sincere entreaties. Traditionally, three rounds of entreaty indicate that an important teaching is about to be expounded, and point to the Buddha's profound determination that this teaching should be spread. In the case of the "Life Span" chapter, however, it does not end with only three entreaties. The disciples' seeking spirit, like a torrent, truly knows no bounds. In response, the Buddha begins to expound the supreme teaching. The fact that the disciples entreat the Buddha to expound his teaching a fourth time indicates that the teaching of the "Life Span" chapter far exceeds the Buddha's other teachings. At the same time, it also suggests that the disciples' determination was so profound as to move the heart of the mentor. The repetition of the phrase "at that time" to mark the developments in the exhortation and response between the Buddha and his disciples at the outset of "Life Span" also conveys a heightening spiritual unity of mentor and disciple. The "time" of the "Life Span" chapter is the moment when mentor and disciple become one in mind. It is the time of the oneness of mentor and disciple. At that "time," there is a perfect concordance between the mercy of the mentor and the determination of the disciples, the wisdom of the mentor and the earnestness of the disciples, the expectations of the mentor and the growth of the disciples. This "time" of perfect unity of mentor and disciple is the time when a broad path is opened up for the salvation of all human beings throughout the eternal future. Based on this pattern of question and response in the "Life Span" chapter, in the Gosho 'The True Object of Worship" [which is written in a question - and - answer format], it is only after the hypothetical questioner has persisted in asking the same key question four times that Nichiren Daishonin clarifies the nature of the true object of worship for the entire world (cf., MW-1, 77-80). Thus, from the standpoint of the Daishonin's Buddhism, it could be said that in this passage at the opening of the "Life Span" chapter the original Buddha, Nichiren Daishonin, is admonishing his disciples to believe in and accept and to practice the Buddha's "truthful words" Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. When we recite this passage during gongyo each morning and evening, we are in effect vowing to advance kosen-rufu in accord with the spirit of the original Buddha. Every day we pledge to the Daishonin, 'Without fail, I will believe in and spread the teaching of Nichiren Daishonin and help lead all people to enlightenment." A person of seeking spirit, of ardent vows, is a true disciple. Ours is a practice of boundless seeking spirit. We dedicate our lives to our vow to fulfill our missions in this lifetime. The original Buddha solemnly watches over all of our efforts in faith and our actions for kosen-rufu. And he praises us most highly and protects us. Those who live based on boundless seeking spirit and resolute vows never become deadlocked. This is the path of infinite advance. Always together with the Daishonin and always basing ourselves on the Gohonzon, we live out our lives along this path of absolute peace of mind. |

| |

|

|

|

Introduction of "The Buddha Cries, Karmapa Conundrum", by Anil Maheshwari This is the chronicle of rogues in robes, and it has the ingredients of a racy pot-boiler depicting the seamy, uncompromising struggle in which the protagonists - high-ranking and respected Tibetan Buddhist lamas - are embroiled in clashes, machinations and mud-slinging that would better suit the temporal world of crooked politics than the spiritual world to which the top echelons of religious institutions profess to belong. The study unfolds an uninterrupted chain of events and circumstances starting several centuries ago and leading to the present-day Tibetan camps and monasteries in the Himalayas of Nepal and India, Tibet, China as well as to modern Tibetan Buddhist centres in the West. Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug are the four orders of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dala Lama enjoys the status of the temporal leader of Tibet. His religious writs run only in his own Gelug order. Strength-wise, among the four orders, Kagyu has the largest following in the West. The number of its non-Tibetan followers all over the world is over three hundred thousand as per a conservative estimate. Besides, the number of followers of this order in Tibet under Chinese occupation is estimated at one million. The head of the Kagyu order is the Karmapa. On 5 November 1981, the 16th Karmapa died of cancer in Chicago, USA, leaving a network of more than 430 centres world wide, and a money-spinning machine where donations pour in incessantly. Only a reincarnation of the Karmapa can inherit the title. The issue of reincarnation of the Karmapa has the main regents of the Kagyu order at loggerheads. They are divided into separate camps and, at the moment, at least two candidates have vied for the title. One is Urgyen Trinley who 'escaped' from Chinese captivity in January 2000. Shamar Rinpoche, the senior regent of the Kagyu order, has described the escape of Urgyen Trinley Dorje as a Chinese ploy to claim the property of the Karmapa. Situ and Gyaltshab Rinpoches have investigated his antecedents. The Dalai Lama too has put the seal of approval on him. Trinley is supported by several lamas within the school and has been accepted by a section of the disciples of the late Karmapa. Curiously also, though avowed atheists, the Chinese too made a conciliatory gesture towards the faithful in Tibet by recognising Urgyen Trinley. It was the first such endorsement by China since the abortive Tibetan revolt of 1959 against the Chinese Communists. However, the announcement by China stressed that the Karmapas had regularly paid tribute to the (Chinese) emperors of the Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties and had received imperial titles many times. Thus, on the one hand, while China shows a facade of tolerance towards religious tradition, on the other, it is obsessed with creating new evidence of its ancient sovereignty over Tibet and therefore pays special attention to Kagyu matters. The Kagyu order predates the Gelug, the order of the Dalai Lama, by about 300 years. (See Appendix C for more details.) A tame Karmapa under Beijing's control would be a boon for China, as it would allow it to dominate his followers. With the young Karmapa 's acquiescence, China would, at a stroke, legitimise its current claim of rule over Tibet dating back to the twelfth or thirteenth century. It was a near take-over by Communist China of the Kagyu order by proxy in which Chinese political expediency saw fit to create a unanimity of views with the Dalai Lama though the fact remains that the confirmation by the Dalai Lama of Urgyen Trinley as the reincarnation of the 16th Karmapa came a full three weeks before the Chinese approval'. The Dalai Lama's coterie was already itching to settle scores with the Kagyu order. It was also deluding itself with hopes of getting concessions from China regarding the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second in hierarchy in the ruling Gelug order of the Dalai Lama. To the disappointment of the coterie, China did not oblige. The only Buddhist lama who side stepped the Chinese trap was Shamar Rinpoche, the senior regent in the Kagyu order. Brushing aside all overtures of the Chinese Embassy in New Delhi, he searched Trinley Thaye Dorje, a Tibet-born boy and, before declaring him as the reincarnation of the Karmapa, he smuggled the boy along with his parents into India. Trinley Thaye Dorje has been approved by several teachers within the Kagyu order and by a sizeable section of the students of the 16th Karmapa in western countries. India, a secular country, does not interfere in sacerdotal traditions. However, it could not remain aloof from this controversy. The headquarters of the Kagyu order is at Rumtek in Sikkim, a state bordering China, and China till date refuses to recognise Sikkim as an integral part of India. Were the 'Karmapa' recognised by China to be allowed access to Rumtek, the headquarters of the Karmapa in Sikkim (India), the decision would certainly have political repercussions for India. Understandably, India is covertly siding with Shamar Rinpoche while the Sikkim politicians, despite their differences by and large, are kowtowing to Situ Rinpoche, the number three in the hierarchy of the Kagyu order. Isolation has been a distinctive feature of Tibet for centuries. The country's geographical inaccessibility and the genuine desire of its inhabitants to have few contacts with outsiders created an ideal situation for seclusion. However, the asylum of Tibetans in India, Nepal, Europe and America was crucial for the survival of Tibetan culture. Considering that the Tibetans fleeing Tibet had little experience of the outside world, they managed the transition from obscurity to modernism well. But in exile they had to work hard to protect their culture from that of the host countries. This problem was exacerbated by the very success Tibetan Buddhism achieved outside Tibet. Tibetan Buddhism did not isolate itself in exile. Instead, by the late 1960s, it emerged as an active proselytising movement in the West. For people with spiritual inclinations in the West who were not drawn towards the institutionally less embedded Hindu gurus and were more fascinated with 'miracles', Tibetan Buddhism appeared as an authentic and authoritative Asian religious alternative. The present-day loyalties, rivalries, and hostilities among the Himalayan lamas have a direct connection with what happened inside Tibet and also China during the last several hundred years. The Tibetan history presents a tangled web of religion, politics, myths and miracles. It is critical to separate these threads to distinguish facts from fiction. Little wonder, actions and thoughts of majority of Tibetans are governed, to a large extent, by episodes from the past. Tibetologists say that the intervening period between the death of a high lama heading a monastic order and confirmation of his reincarnation has almost always been marked by rivalries, struggles and intrigues - and also, machinations. The whole process of reincarnation of lamas and the metaphysical transmission of religious and temporal authority in a Tibetan monastic order possibly has political undertones. The Nyingma order faced competing reincarnations in 1992. The Dalai Lama backed one nominee as the reincarnation of Dujom Rinpoche, the highest Nyingma lama. On the other hand, Nyingma Chadrel Rinpoche recognised another candidate, and all Nyingma disciples followed their own order's choice. The head of Sakya has always been a tantric practitioner, like the Nyingma lamas. He is allowed to marry and keep his plait of hair. As a true follower of tantric doctrine, he is believed to be a voluntary impotent for he does not discharge semen. However, if he feels it necessary to have a successor, he invites the soul of a dead holy person to enter into the womb of his wife. The present reigning lama Ngawang Kunga Theckchen Rinpoche (Sakya Tridzen) is from the House of Dolma Phodrang. He stays at Dehra Dun in India. Two other lamas from the House of Phuntsok Phodrang work in Seattle, USA. Sakya Lama's priesthood is hereditary. The head of the Gelug order hands over his Ganden throne to a successor chosen by him before his death. The tradition continues till today. The 99th successor of the Ganden throne and the religious head of the Gelug order is Yeshi Dhondup. He lives in exile at the Kaden monastery in Karnataka (India). The main secular function of tulku was to institutionalise the charisma of some individual lamas with extraordinary achievements. The idea is based on the Buddhist (or Hindu) concept of rebirth, which all persons are supposed to undergo after death. However, bodhisattvas, whose reincarnations most of the high lamas claim, are superior beings who are on the threshold of enlightenment but who have deliberately postponed it in order to be present in the world and help the suffering human beings to become enlightened. What has set Tibet apart from the rest of the world is the fact that the country was able to continue the unbroken and living transmission of the teachings of the Buddha. These include the highest instructions about the ultimate nature of reality along with methods of its realisation. And while the average Tibetan goes about his or her business without giving much thought to the highest truth - leaving all such exalted matters to the attention of their lamas and institutions - a small number of individuals use the unique techniques available and achieve better results. Out of a few million people, a precious handful of lamas and yogis are able to fulfil, generation after generation, the highest potential of the human mind. As such, Tibetans believe that such high lamas have a certain degree of freedom over death and rebirth, especially when it comes to when and where to be reborn. It is this mysterious jigsaw puzzle that lamas try to solve after the death of every high lama through dreams and visions, oracles and divinations, mysterious signs and close observations. The Karmapa has kept coming back in an unbroken sequence of embodiments that has spanned 900 years till now. Similarly, other highly realised lamas started to reincarnate consciously and were then recognised by their accomplished disciples. Life after life, a lama's enlightened qualities came into contact with his students. Hundreds of different tulku lines manifested throughout Tibet and the whole system served as a unique mechanism for preserving an unbroken transmission of the Buddha's teachings. Over the centuries, however, monasteries and their tulkus have grown in wealth and wield considerable influence over the social and political life of the country. A number of tulkus have assumed the role of political figures augmenting their role as religious teachers. To locate and deliver the new reincarnation of a prominent tulku to his old monastery means gain of power. Since in many cases the criteria according to which reincarnates are recognised leave much room for manoeuvre, the process becomes an instrument for political infighting. The traditional method of scrutiny whereby the young hopefuls have to identity objects belonging to the predecessors is often bypassed. Outstanding masters are not always consulted. Political influence, money or the edge of the sword have become the decisive factors instead, and the rank of authentic tulkus has begun to dwindle. It is not at all uncommon to have two or more candidates - each backed by a powerful faction - openly and violently challenging a well-known tulku seat. While the young aspirants may have little idea about the fray that goes on behind their backs, their mighty patrons are even ready to go to war to see their choice prevail Once the throne of a tulku for a contestant is won, his education begins, strictly in accordance with the role he has to play in his mature years. Surrounded by an all-male entourage of hereditary tutors and servants, the young reincarnate is generally subjected to severe discipline and left exclusively in the custody of his circle of zealous attendants. This is to enable the tulku to receive a transmission of the Buddha's teachings in its purest form, as much as it is to guard him as the monastery's most valuable possession. More often than not, consequently, the seclusion results in the tulkus somewhat vague knowledge about life outside his monastery's walls. At the same time, those around him play a far more dominant role than the benefit of his seat would require, pursuing sometimes their vested interests over the head of their master. Such a state of affairs is, of course, fertile ground for foreign interference. With foreign as well as domestic meddling close at hand, the religious choice for a tulku has, over the centuries, become an exception rather than the rule. Authentic lamas have, of course, manifested. Tibetan history is rich in examples of highly accomplished tulku lines and, in theory, the whole system is geared towards bringing forward and taking care of such things. Yet, the same system, after centuries of abuse, has allowed a great number of reincarnates to become political puppets or absolute princes. They become instruments in the hands of their households whose members, while fervently guarding access to the former 's ears, scheme their own intrigues. Reincarnates often behave like politicians and remain accountable to none. Advised by whosoever has gained their favour, they plunge often unprepared into the choppy waters of political passion. As a consequence, a throng of inept individuals often governs the affairs though their only qualification is the possession of a title or affiliation to a name. The narrative that follows is to be perceived against this particular setting. The inflammable mixture of a touch of personal animosity, hostility and, eventually, hatred has added spice to an otherwise dry historical process. The emerald-green mountains and the snow-white clouds above the Rumtek monastery turn dark gray as sunlight dissolves, in the distant horizon. The deepening darkness renders the base murky. The bells toll a sombre note and the traditional ornate gongs resound at a slow and graceful pace. The multi-hued prayer pennants flutter in the gentle breeze that whiffs around the majestic monastery nestling on the mountain. An air of oriental mysticism pervades the place and spontaneously evokes feelings of deep devotion and awe. Tibetan ascetics and their disciples are there. So are the murals, tapestries and thankas (scroll paintings) embroidered with traditional and religious motifs. But, the pristine serene atmosphere of the gompa has soured to the extent that it seems to be beyond redemption. The canker has set in and, like gangrene, inch by inch, the flesh is putrefying though the spirit is ever so willing. |

| |

|

|

|

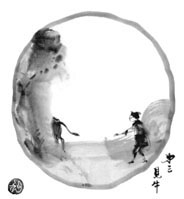

An Introduction to Zen:Precepts, The Everyday Acts of Buddhas"Religious Practice for Everyday Life": Precepts: The Everyday Acts of Buddhas Scripture: Receiving the Precepts. After recognizing our evil acts and being contrite therefor, we should make an act of deep respect to the Three Treasures of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha for they deserve our offerings and respect in whatever life we may be wandering. The Buddhas and Ancestors transmitted respect for the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha from India to China. I think there is a bit in the Bible somewhere which says that a man cleans up his house and comes back (all the demons are out of it), and he comes back and its empty and clean, and Oh, its boring: theres nothing in here. So he goes out and gets a few more demons to bring in, because theres nothing there. The instant you have done this act of contrition we are talking about here, you must take immediate refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Otherwise you will be casting about for something to take the place of all this stuff. Now, you've just got rid of it; who wants to scrub the house twice? Dogen makes it very clear: you've got to get the Buddha in there immediately. Faith, study, trust: they must take the place of the karmic baggage. You must get that in at once. Scripture: If they who are unfortunate and lacking in virtue are unable to hear of these Three Treasures, how is it possible for them to take refuge therein? One must not go for refuge to mountain spirits and ghosts, nor must one worship in places of heresy, for such things are contrary to the Truth: one must, instead, take refuge quickly in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha for therein is to be found utter enlightenment as well as freedom from suffering. The main heresy of which they are speaking is teachers who say that if you find enlightenment (They usually dont say the Eternal because that smacks too much of the word God), you are totally free to do whatsoever you wish. This is why, when I teach Zen, the most important thing first of all is for me to speak of the Eternal, and the second thing to speak of faith, study and trust, and the third thing, responsibility. You need to talk about these things before somebodys got so involved in meditation that the baggage they've had is starting to come up and they're getting terrified out of their wits as to what happens. We had a lady come to Shasta on one occasion for a retreat, which is a meditation weekend. She was Christian, and she had never meditated before; she learned very fast, and that day a whole bunch of past life stuff popped out. She was terrified, because with her Christian background this could only be a bunch of demons, and what was this stuff that was coming up? Before anyone sits down to meditate (which is why I spoke to you the way I did yesterday), you must know that everything hidden will come up and that its normal, and not be scared of it. And that it doesnt alter, it doesnt damage, your belief in God or anything else: you just must do something about realizing it takes place, not get worried about it, and be willing to look at it honestly and make some changes in your life. Okay? Scripture: A pure heart is necessary if one would take refuge in the Three Treasures. At any time, whether during the Buddhas lifetime or after His demise, we should repeat the following with bowed heads, making gassho: I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Dharma, I take refuge in the Sangha. We take refuge in the Buddha since He is our True Teacher; we take refuge in the Dharma since it is the medicine for all suffering; we take refuge in the Sangha since its members are wise and compassionate. And the Sangha includes the laity. Scripture: If we would follow the Buddhist teachings, we must honor the Three Treasures; this foundation is absolutely essential before receiving the Precepts. Yes, there has to be faith. You have to know that what you study, the Dharma (which comes forth from the Dharma Cloud, the cloud that hides the Eternal from our sight, as we say), is the medicine for all our ills. Remember: the Buddha That Was to Come was the Doctor Buddha who had cleaned up all His ills. We have to know that we can clean up all our ills, and we have to know that there are wise and good people who can help us. So, the taking of the Three Refuges is essential: it is the only thing that is really a formalized prayer, if you like, in every school of Buddhism. After that, they all have differing bits and pieces, but this one is common to every single school. Scripture: The merit of the Three Treasures bears fruit whenever a trainee and the Buddha are one; whoever experiences this communion will invariably take refuge in the Three Treasures, irrespective of whether he is a god, a demon or an animal. Now what they're talking of there is that whenever the trainee and the Buddha are one, whenever a trainee finds the Eternal, that refuge is immediately cemented. Scripture: As one goes from one stage of existence to another, the above mentioned merit increases, leading eventually to the most perfect enlightenment: the Buddha Himself gave certification to the great merit of the Three Treasures because of their extreme value and unbelievable profundity it is essential that all living things shall take refuge therein. Now, the Three Refuges taking refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha are also called the First Three Precepts. Then come the Three Pure Precepts: cease from evil, do only good, and do good for others. Now these are not as obvious as they seem on the surface. Cease from evil: everyone can understand the words of that, but not everyone knows what is. Ceasing from evil is a collective precept about refraining from harming other beings that comes about as a result of having evil analyzed out into the Ten Precepts, which we will come to later. If you like, these Ten Precepts telescope into ceasing from evil. Dont kill, dont steal, dont covet, etc.: these are what bring about evil. You have to look at that. So, ceasing from evil, doing only good, and doing good for others are the Three Pure Precepts. One has to also know what doing only good is, because doing only good for some is one thing and doing only good for others is another thing. Again, you have to take the Ten Precepts and telescope them into that. You then have to take the last one, which is do good for others, and that is much more complicated, because what it really means is dont set up some karmic thing or other that will cause others to do wrong, just because you think its good. The example I gave of what was done at the end of World War I is an exact example of that. That is going to bring about horrendous horror. You mustnt set up a chain of causation that will influence others to cause great harm. So you have to fit all the Ten Precepts into that one as well. So if you start with the Three (cease from evil, do only good, and do good for others), you can literally turn telescope them upwards into the Three Refuges and downwards into the Ten Precepts. Because if you dont have faith in the Buddha, youre never going to be able to do this; if you dont have places where you can find out what good is and what bad is, and what evil is and all the rest of it, which is the Dharma, you wont have a rule of thumb to go by; and if you just think you are always right and never go and ask anybody, which is to take refuge in the Sangha, you will never get beyond your own opinions about all this. So, the Ten Precepts telescope up into the Three Pure ones, and they, in turn, telescope into the Three Refuges. Scripture: The Three Pure, Collective Precepts must be accepted after the Three Treasures; these are: Cease from Evil, Do Only Good, Do Good for Others. The following ten Precepts should be accepted next: 1. Do not kill, 2. Do not steal, 3. Do not covet, 4. Do not say that which is untrue, 5. Do not sell the wine of delusion, 6. Do not speak against others, 7. Do not be proud of yourself and devalue others, 8. Do not be mean in giving either Dharma or wealth, 9. Do not be angry, 10. Do not debase the Three Treasures. Now, the Kyojukaimon1 will speak of these in great depth. But the thing that each one telescopes into is very interesting. If you steal, in the end you realize that you stole from yourself. If you kill, you realize that you made yourself less than human. If you covet, you realize you have stolen your own peace of mind, because you are never contented. If you go against any of these precepts, the person who you harm, besides others, is yourself. Why do you make clouds in a clear sky? Do not make clouds in a clear sky. When you realize that all of this is soap opera that you have created in what was a very, very clear sky, you can start to see how to deal with these things. The First Noble Truth of Buddhism is that suffering exists: there is birth and death how do I escape from it I am so frightened etc. Suffering exists: pain, grief, illness, misery, family problems they are all suffering. How do you deal with this, then? Suffering occurs because of a not understanding of the precepts, a non-keeping of the precepts. You take a look at yourself thoroughly as the stuff comes up in meditation, and you deal with it. The end of suffering comes when you find the Eternal and realize that the only way to live is by keeping the precepts. But you cant keep them in a nice, neat package, because they are always impinging on each other, so the aim has to be to do only good, to cease from evil, and to do good for others by not causing them to do evil. Now, there are different forms of these precepts in Buddhism, which is something a lot of people misunderstand. For instance, the oldest form is, I promise to undergo the rule of training to teach myself to refrain from.... Think of the amount of qualifiers on that: theres a tremendous difference between that and Thou shalt not. I promise to undergo the rule of training to teach myself to refrain from killing or ...to refrain from stealing, or ...from talking against others. Another example of a different form occurs on the precept: dont sell the wine of delusion. One form of this one is to refrain from abusing alcohol or drugs, and a lot of people think this is all it means. It isnt. It is also saying, If you delude other people with your theories and your opinions, they will become drunk on those theories and will not be able to use their own minds to see what is really going on. If you like, it is a precept against brainwashing. Do not sell or spread the wine of delusion: a very important piece of Buddhist teaching. Now, in applying these precepts, you bump into all sorts of complications. Would it be wiser to tell the truth in a certain circumstance and perhaps speak against someone? Would it be wiser not to tell the truth and not hurt them? What is the best way to go? The answer is: absolutely cease from evil; do everything with the best of intentions. That you may or may not make mistakes is another matter. All the Ten Precepts are subject to this very careful scrutiny: what am I doing; am I doing the right thing; am I doing the best thing? Sometimes we have to break one precept in order not to do something much worse. Whether we break that precept or not, we are going to take the karmic consequences of what we do; we are going to grow some more karmic consequence. If we break one precept, we will take the consequences of breaking that precept, which may be a lot less than the consequences of not breaking it, because we would have then done something much worse. Once again: Buddhism is for spiritual adults; it is not for spiritual children. The Ten Precepts tell you what can cause karma; then you have to work out how to combine them properly so as to cause as little karma as possible. So, there is no such thing as irresponsibility in Buddhism. You have to be a terribly responsible person or you cannot be a true Buddhist. And you have to be willing to take the consequences of every action. Furthermore, you have to mix and match your precepts so that they will telescope nicely into the Three Pure Precepts. When people say to me, How do I behave? What do I do? I say, Well, you ask yourself three questions. First, are you ceasing from evil? If you get a yes to that, you can go on and ask the second question: am I doing only good? If you get an answer that says yes to that (and you ask these questions in the mind of meditation), go on to the next one: am I doing good for others? And if you get an answer that says yes to that, then go ahead and do it. And you could still be wrong. important to know that you could still be wrong, because you might have got yourself in the way of it. So, because you always could be wrong, you then go and see a member of the Sangha. Whether that is a relative, a friend, or a priest, go and see someone who is outside of the situation and can perhaps help. There is a saying in Zen, When we find the source of the Yellow River, it is not pure. This means that however hard we try, nothing ever comes out quite as clean as we like it. (laughter) Keeping this in mind, remember that the person who gets hurt if you break the precepts is always you. If you go through the Kyojukaimon in detail, you will see how these things can harm you. It is you that gets hurt, along with a lot of other people. In other words, you've made a thunderstorm in a clear sky, which is an awful shame. Now, how do you start putting these precepts into practice? Sometimes living by the precepts seems like such a daunting task that there's no point in even trying. Well, you start by simply saying, Okay, for today I am going to try to keep this precept, or that precept. I tell people, if they've never done it before, to pick one, and not pick the hardest, and see how well they can keep it for the day. I learned this from the Chinese; I really admire their practicality. There is a set of ceremonies called Jukai [the formal taking of the precepts] in all Buddhist countries, and only in China is it possible for you to take as many precepts during that time as you really feel you can keep. For example, a butcher would not take the precept against killing. A merchant usually does not take the precept against stealing, which I found faintly funny, and you will find prostitutes who will not take the one against sexual indulgence, and that is understood. So start by taking one you can keep and, having discovered the joys that come from keeping one, you work from the known to the unknown. And it is surprising what happens: several of the female monks who were in the monasteries had been former prostitutes who, having suddenly discovered the joy of keeping one or two, said, I think Ill try to do a few more. Choose one you can go with; dont start the hardest way possible. Look at your character (only you can know your character thoroughly) and choose the one that is best for you, and thats the one you start with, and see how well you can keep it. I used to love gossip at one time, and I can remember that I decided the one I was going to start with was talking about others, and I discovered that for three days I didnt say a word! (laughter) Which showed me how much wasted breath Id been coming out with, and then I started thinking about how to talk to people and about what was truly useful conversation. So you start from the known and work to the unknown, and by keeping one precept you end up keeping the whole lot, and you end up knowing the Eternal, and thats really what you're out to do. The fourth of the Four Noble Truths that the Buddha found was the Eightfold Path. Having got to the state where you've cleaned things up, you've dealt with the cause of suffering, now you come to the cessation of suffering, which is taking the precepts absolutely to the very best you can and being willing to always telescope them into each other and to go for help as needed (whether that be study, faith, or finding someone who can help you). When you've done that, then you can go on to what is called the Eightfold Path. That Path is the fruit of preceptual living: Right Thought, which leads to Right Speech, which leads to Right Action, which leads to Right Activity, and Effort and Determination and so on through the eight. Which comes back in the end to Right Meditation, which is why you need to meditate night and morning even if its only for a couple of seconds: it puts your brain in gear for what goes on elsewhere. If you put your brain in gear for only a few seconds or a few minutes, the day will be much, much better from every angle. Scripture: All the Buddhas have received, and carefully preserved, the above Three Treasures, the Three Pure Collective Precepts, and the ten Precepts. If you accept these Precepts wholeheartedly the highest enlightenment will be yours and this is the undestroyable Buddhahood which was understood, is understood and will be understood in the past, present and future. Is it possible that any truly wise person would refuse the opportunity to attain to such heights? The Buddha has clearly pointed out to all living beings that, whenever these Precepts are Truly accepted, Buddhahood is reached, every person who accepts them becoming the True Child of Buddha. On that note (which I dont need to explain at all because you are then one with the Eternal, at least until you break the precepts again, at which time you have to do something about it and then you are back), we will break for a few minutes. I told you this one was going to take a long time. [pause for rest break] Now, can we have the next bit, please? Scripture: Within these Precepts dwell the Buddhas, enfolding all things within their unparalleled wisdom: there is no distinction between subject and object for any who dwell herein. All things, earth, trees, wooden posts, bricks, stones, become Buddhas once this refuge is taken. From these Precepts come forth such a wind and fire that all are driven into enlightenment when the flames are fanned by the Buddhas influence: this is the merit of non-action and non-seeking; the awakening to True Wisdom. This describes what happens at the time of finding the Eternal: the realization that you are beyond the opposites; there is no-thing that is outside of the Eternal, no-thing in this world that is not part of the Eternal, no-thing in the universe that is not part of the Eternal. And the wind and fire, well, if you meditate properly, youll find out about the wind and the fire. It is after reaching this viewpoint that we really commence true training. It is when you have reached the realization that everything is doing the finest job it can of being a Buddha that you are open enough and positive enough to be able to do really good training. While you are still nagging and grousing and griping about everything, you are mostly just spinning your wheels. But it is when you start looking positively and saying, Well, if so-and-so knew better, he'ld be doing better, so he is showing his Buddhahood to the best of his ability at the moment instead of griping about how he is, it is when you start seeing that the carpet is nice and warm for you to sit on rather than seeing the spot that is on it, it is when you start seeing the good, the Buddhahood, in things, that true training can commence in earnest. It is the same with the precepts: while the precepts are only rules that bind, not very much can be done, which is the danger of the Thou shalt not idea; but once you have got to the positive side, once you have given up fighting these things and seen the Buddha within them, true training has well begun. Ten Ox-herding : PERSON AND OX BOTH FORGOTTEN At the eighth stage, "person and ox both forgotten"[jingy gub], we come to realize the fact that this "I" (person), which has been seeking, and the essential self (ox), which has been the object of our search, did not exist at all. It is the same fact manifested in D´gen Zenji's statement, "My body and mind have fallen away," which he presented to his own master, TEND Nyoj´ Zenji [1162-1227], after he had come to great realization upon hearing the words of his master, "Practicing Zen is the falling away of body and mind." You have forgotten yourself, you have forgotten all others, you have forgotten everything; there is only one round circle without any substance whatsoever. This is what is meant by "person and ox both forgotten." In order to reach this stage, it is of crucial importance that - as a saying goes - "you do not linger where there are buddhas, and you pass quickly through where there aren't any buddhas." To "linger where there are buddhas" means to idle your time away with such beloved concepts as "buddhas," "enlightenment," and so on. As long as you cherish in your mind even a little bit of such ideas as "kenshƒ," "great enlightenment" [daigo tettei], "Dharma transmission" [inka shmei], and so forth, you are not yet a true one. "Where there aren't any buddhas" means, on the other hand, a level of mind where you can say that such seemingly precious items concern you no more. But you must never foster this notion in your head or even take pride in this fact. You must "pass quickly through" it. Explaining the seventh stage "Ox Forgotten, Person Remaining," I mentioned that there still remains self-consciousness. It was because the person was leisurely dwelling on the level of "no buddhas." When you have passed through this level, the world where there is utterly nobody and nothing becomes truly clear and evident. If you have passed beyond both the world of buddhas and that of no buddhas, you are in a world which even Shakyamuni or Manjusri with their clairvoyance cannot perceive. It's because there is not even a thing there. The basis of Zen is to grasp this world of nothingness through experience. Zen without this experience is merely a conceptual Zen and amounts to nothing more than playing around with plastic models of Zen. If someone has truly experienced the real fact, how would his life look? Let me show you an example. In ancient China there was a Zen master named GOZU H [594-657]. He was a man of high virtue, and people in his neighborhood respected him deeply. Even birds praised his virtues by fetching flowers and offering them to him. But later on, after he came to great enlightenment under the Fourth Patriarch DAII Dshin Zenji [580-651], the birds stopped bringing flowers to him. As long as people extol you as a great person, a person of high virtue, etc., you are not real. A person of true enlightenment does not look great at all. The birds fail to spot H Zenji, because he turned invisible to them, as he became someone who is nowhere. Let's now appreciate the verse composed by Kakuan Zenji: (a)Whip, tether, person and ox - all are empty: You have diligently applied whips and tethers, searching with all your might for your essential self. Your goal once attained, you realize that the whips, tethers, you yourself and the ox - all is empty with no substance at all. It is a world where there is utterly nothing and no one. (b)The blue sky spreads out far and wide, it cannot be communicated: The blue sky is wide and clear. It expresses the true fact of emptiness, the world of true self. Since it is empty, there is no means to communicate it. Yet, to tell you the truth, it was communicated from the very beginning as "empty." (c)On a red-hot oven, how can there be any place for snow? The "red-hot oven" is a live blast furnace burning with scarlet flames. It melts away anything. It goes without saying that snow will be made to evaporate in an instant, leaving no trace whatsoever. It means that the true fact of emptiness is burning hot like the furnace. There is no room for any discriminatory thought ("snow") to enter. (d)Having come this far, you understand the intention of the patriarchs: Only at this level, you match the spirit of buddhas and patriarchs. In other words, if you don't attain this level, there is no meaning in your Zen practice. Only with this experience can you solve your problem of life-and-death and attain true peace of mind. However, it is still the eighth stage of practice; you need to practice more to come up to even higher levels. |

|

|

|